Racist Policing

Overview: Through racist policing practices like racial profiling and designating certain neighborhoods as “dangerous”, racialized and migrantized communities are systematically criminalized. Courts consistently fail to scrutinize or hold law enforcement accountable for such practices, readily accepting police testimonies at face value even when their accounts are unreliable. Further, court observations frequently bring to light how police act in violent or discriminatory ways against racialized persons during controls leading to an arrest or a complaint for a different offense. The fact that policing affects different population groups differently is systematically obscured by the courts, since their own legitimacy is wrapped up in the idea of a supposedly “neutral” legal system.

Racist policing is a structure, not a series of “isolated incidents.” To understand this is to recognize that one of the police’s core functions is to uphold and enforce a social and economic order that demands racist hierarchy. As the theorist and activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it: “Capitalism requires inequality and racism enshrines it.”1 In our society, the police are tasked with protecting this arrangement, to ensure the smooth functioning of the system. Their work is “domination work”, which means that it affects different population groups differently, depending on how they are positioned within social power relations.2 While affluent white subjects can and do rely on the police for protection, racialized, poor, and migrantized subjects, for example, cannot. Their domination is baked into how the system operates. Racism, therefore, is baked into the police’s social function as well as into their operational logic, which is a distinctly differential one.3

One of the primary mechanisms through which racist policing operates is the practice of racial profiling. As the social scientist Vanessa Thompson has detailed, random identity checks based solely on assumed identity violate the German Basic Law (Art. 3 para. 3 GG), the General Equal Treatment Act (AGG), and the prohibition of racial discrimination laid down in the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Convention against Racism.4 Nevertheless, affected communities experience these practices routinely, and organizations like KOP (Kampagne für Opfer rassistischer Polizeigewalt) have documented racial profiling and other instances of racist policing for decades.5 One reason why racial profiling persists is that certain police regulations provide loopholes for racial profiling. For instance, identity checks independent of suspicion or cause are permitted in border regions as well as in areas the police designate as so-called “dangerous places” or “crime hotspots.”6 In this way, the illegal practice of racial profiling can proceed under a cloak of legitimacy.7 In recent years, the racist construct of “clan criminality” has further served to mark racialized communities and businesses as targets for increased surveillance and control.8 These practices shape who ends up in court. Racialized and migrantized populations are overpoliced and therefore overcriminalized.

Beyond these structural and systemic features of racist policing, research also shows that racist attitudes permeate police in Germany on an institutional level.9 Racist prejudice affects how individual police do their jobs, leading to discriminatory behavior toward suspects as well as aggrieved parties when they are racialized. Racist policing extends also to other actors beyond the institution of the police, which is another point that KOP and their founder Biplab Basu have long emphasized:10 Jobcenter employees, security guards, schoolteachers, store detectives, and others all engage in racist policing as well when their acts of surveilling, detaining, and/or sanctioning primarily target racialized communities.

Such practices from police and other actors are rarely (if ever) interrogated in court. We observe that judges routinely hold police witnesses in high esteem, placing unusual amounts of trust in their accounts—even when police themselves admit to their testimony being unreliable.11 Judges do not hold police and security personnel accountable for their controlling methods, even when these are suspect.12 This obscures the context in which a given offense may have taken place and the broader structural dynamics at play. For instance, when someone is tried for an offense alleged to have taken place in an area known to be highly policed, we observe that courts do not interrogate whether an arrest was the result of racial profiling, thereby legitimating and further entrenching the practice of hotspot policing and the racist logic of differential policing this practice facilitates. Procedural decisions like penal orders and fast-track-proceedings without legal counsel systematically enable such practices to go unchecked. Further, we also observe cases where police appear as violent actors or abuse their power in other ways against racialized defendants, some of whom choose to bring this into focus during trials, at times enlisting the support of activist organizations such as ReachOut.13

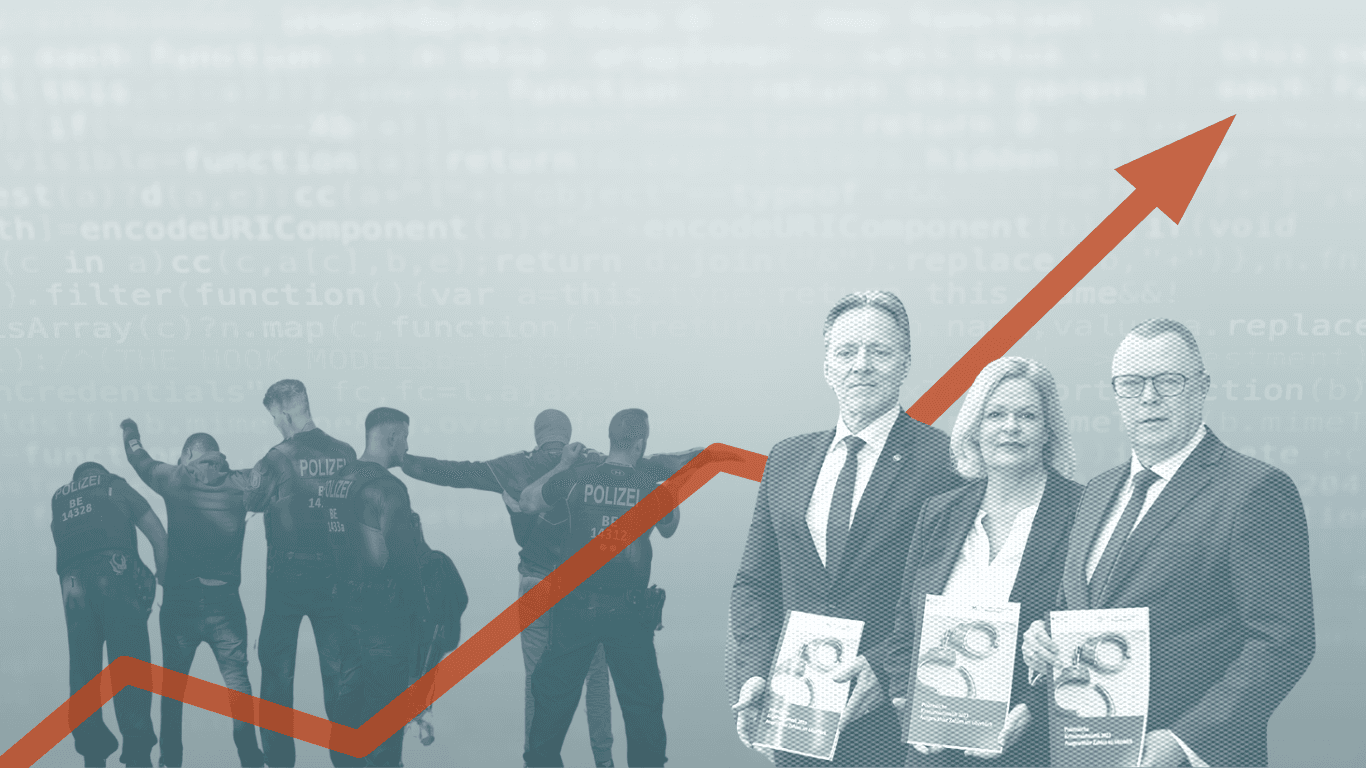

The fact that policing affects different population groups differently—and that these differences are racialized—is systematically obscured by the courts. This is because their own legitimacy is wrapped up in the idea of a supposedly “neutral” legal system. At the same time, convictions fuel rampant racist discourses around so-called “foreigner crime”, alleging that migrants are more prone to criminality than Germans, who are implicitly racialized as white. When the structural problems behind racialized and migrantized people being overcriminalized are thus misrecognized, this feeds a self-reinforcing cycle in which politicians can present more policing and stricter policing as a solution—with foreseeably harmful consequences. In our case archive, we tag cases as structured through racist policing when we observe these differential dynamics unfolding—for example when police, store detectives, or other security personnel appear to draw on racial profiling practices; when victims of racist police violence are construed as perpetrators and held responsible for their efforts to resist; or when police act in violent or discriminatory ways against racialized persons during controls leading to an arrest or a complaint for a different offense.

Citations

- 1

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, ‘The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement’ in Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (Verso 2022), 451.

- 2

Hannah Espín Grau, ‘Art. 19 IV und Art. 20 III GG: #Polizeiproblem im Rechtsstaat’ in Auerbach, Moissiadis, Schramm, Schuch, Thurn, Wegemund (eds) Unrecht mit Recht?: Ein Reader zu Nationalsozialismus und juristischer Ausbildung (AK Zeitgeschichte und Ausbildung 2024), 90.

- 3

Daniel Loick, Zur Kritik der Polizei (Campus 2018).

- 4

Vanessa Eileen Thompson, ‘“Racial Profiling”, institutioneller Rassismus und Interventionsmöglichkeiten’ (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 27.04.2020) <https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/kurzdossiers/migration-und-sicherheit/308350/racial-profiling-institutioneller-rassismus-und-interventionsmoeglichkeiten/>. See also Thompson, ‘Rassistisches Polizieren. Erfahrungen, Umgangsweisen und Interventionen’ in Daniela Hunold and Tobias Singelnstein (eds), Rassismus in der Polizei: Eine wissenschaftliche Bestandsaufnahme (Springer VS, 2022).

- 5

KOP- Kampagne für Opfer rassistisch motivierter Polizeigewalt, ‘Chronik rassistisch motivierter Polizeivorfälle für Berlin von 2000 bis 2023’ <https://kop-berlin.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Chronik.pdf>.

- 6

Thompson, ‘“Racial Profiling”, institutioneller Rassismus und Interventionsmöglichkeiten’.

- 7

See, for example, Svenja Keitzel and Bernd Belina, ‘“Gefährliche Orte”: Wie abstrakte Ungleichheit im Gesetz eingeschrieben ist und systematisch Ungleichbehandlung fördert” (2020) 110 (4) Geographische Zeitschrift.

- 8

Mohammed Ali Chahrour, Levi Sauer, Lina Schmid, Jorinde Schulz, Michèle Winkler (eds), Generalverdacht: Wie mit dem Mythos Clankriminalität Politik gemacht wird (Nautilus, 2023).

- 9

Matthias Monroy, “Die Polizei ist rassistisch” (nd 09.09.2024) <https://www.nd-aktuell.de/artikel/1185113.strukturelle-diskriminierung-die-polizei-ist-rassistisch.html>.

- 10

See, for instance, Biplab Basu and A.v.K., ‘Das Gesamtbild ist rassistisch - Rassismus und Justiz’ in Angelina Weinbender, Iris Rajanayagam, Mahdis Azarmandi (eds), Rassismus und Justiz (Migrationsrat Berlin-Brandenburg e.V. 2014).

- 11

- 12

- 13

Cases from our archive

Case 13

A man appeals a fine that was imposed on him because two police officers claim to have seen him holding a phone in his hand while driving. The officers have no recollection of the specific event, but the judge affirms the fine based on their statements. The defendant faces additional costs of around €300 as a result of the appeal to the fine on top of the €100 fine.

Case 3

A young migrantized man is held in pretrial detention for four months and is ultimately convicted, based on his confession, of stealing a pack of cigarettes and a lighter. The judge sentences him to time served, apparently avoiding paying him reparations for his lengthy pretrial detention.

Case 21

The court puts pressure on a man to revoke his appeal of a conviction for resisting arrest and assault of police. Despite the defendant’s distress, the judge appears uninterested in the man’s account of the alleged offense. The outcome–no relief for the defendant–appears predetermined by the judge, prosecutor, and the defendant’s attorney.

Case 16

A young man is sentenced to insult for statements during a police control. The court does not take into account the man’s apology or experience of the control as discriminatory. He is threatened with a harsher sentence and so accepts the high fine he had appealed.

Perspectives

Die polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik ist als Instrument zur Bewertung der Sicherheitslage ungeeignet

Justice Collective, Grundrechtekomitee und 40 weitere

Wissenschaftler*innen und Mitglieder der Zivilgesellschaft warnen vor der politisierten Nutzung der polizeilichen Kriminalitätsstatistik, die jedes Jahr dafür genutzt wird, falsche Narrative über steigende Kriminalität und vermeintlich „kriminelle Migrant*innen“ zu verbreiten. Die Unterzeichnenden stellen das durch das BKA und die Medien gezeichnete statistische Bild entschieden in Frage und betonen, dass die PKS zur Polarisierung der Gesellschaft und Stigmatisierung bestimmter Bevölkerungsgruppen beiträgt.

Documenting racism in court: Interview with Justizwatch

Justizwatch

An interview with Justizwatch on their work documenting racism in court in Berlin.

Solidarity-based interventions in systems of racist violence: policing, punishment, and (mass) criminalization

Kampagne für Opfer rassistischer Polizeigewalt (KOP)

The intensification of state repression, marginalization, and militarization are currently leading to an increase in police violence, a rising number of arrests for poverty-related offenses, and the brutal (criminal) disciplining of “internal enemies”. In this situation, it is urgent to reflect on how we can link the fight against racist police violence and state racism more closely with other struggles to end dehumanization, exploitation, and widespread state violence.