Criminalized: The Anti-Migration Debate Fuels and Legitimizes Systemic Racism

Anthony Obst, Justice Collective

In recent weeks, millions of people across Germany took to the streets once again in protests against the far-right. Yet, all leading parties continue to outdo each other in the election campaign with racist policy proposals usually associated with right-wing extremism. The CDU’s 5-point migration and security plan, supported by the AfD and FDP, was followed by a 10-point plan from the Greens, which also called for more control, surveillance, and detention of migrants and asylum seekers, as well as more deportations and an “enforcement offensive” to arrest people with outstanding warrants. Meanwhile, in the televised debate of chancellor candidates, Olaf Scholz boasted about his government’s “accomplishments” regarding border controls and deportations, promising that this “tough course” with stricter laws and the expansion of pre-deportation detention would continue under a new SPD-led government.

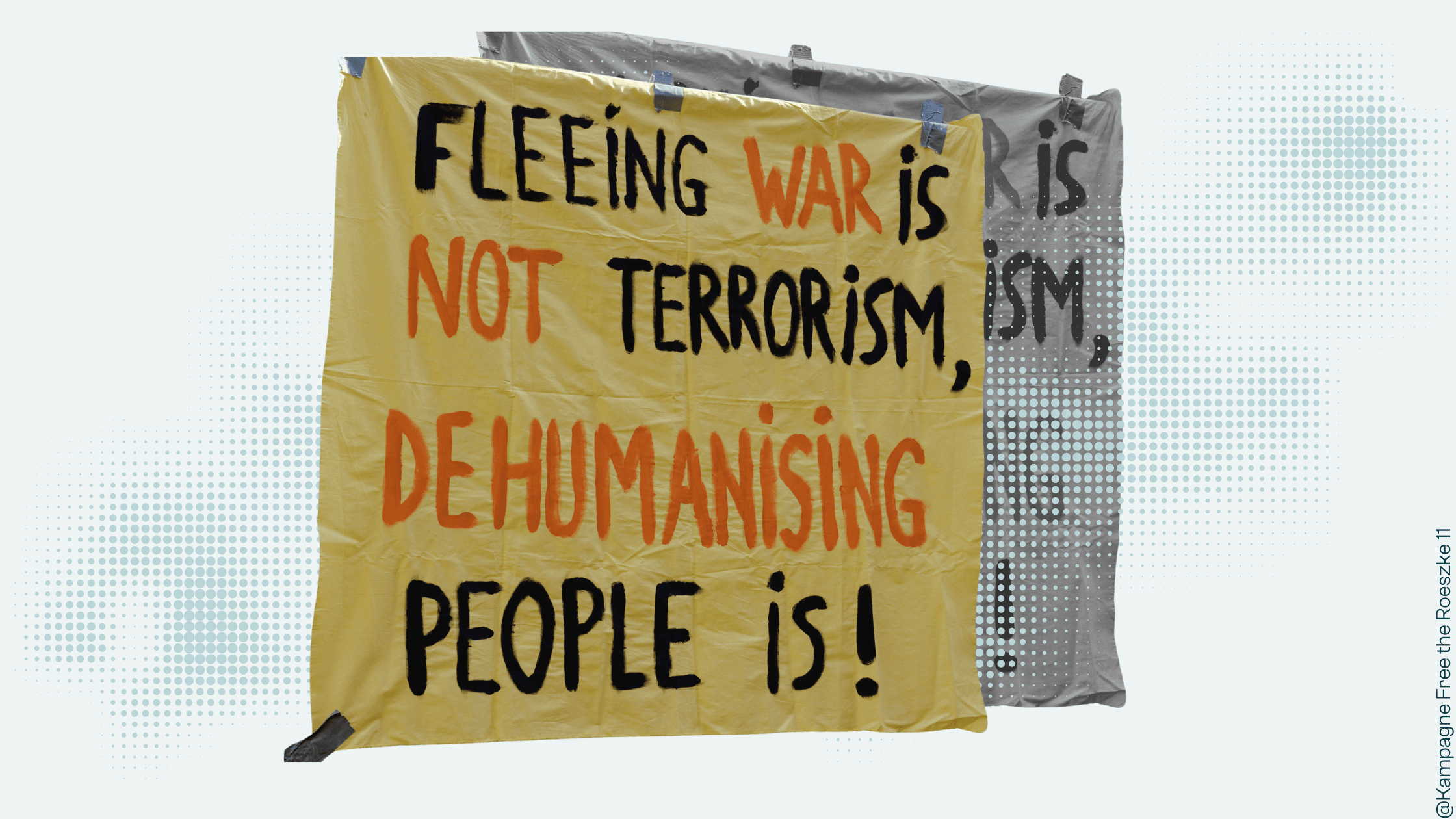

This preelection trend is deeply concerning: almost all parties have agreed to treat migration exclusively as an alleged security problem. The conflation of migration and supposed security issues has shifted political discourse to the right, displacing social questions about better living conditions for migrants and people affected by poverty. Fueled by media coverage of isolated violent incidents, a troubling consensus has emerged that presents increasingly severe law-and-order measures as the only solution to perceived insecurity supposedly caused by immigration. In parliamentary politics, this racist logic is now virtually unchallenged.

Carceral racism: a form of normalized state violence

Many people already suffer the consequences of this approach. Punitive measures, surveillance, and exclusion that systematically disadvantage racialized people (which can also be described as “carceral racism”, as explicated by Vanessa E. Thompson) have long been normalized in Germany. This form of racist state violence manifests not only in rising deportation numbers but also in practices like disproportionately detaining non-Germans for minor offenses like shoplifting—often for many months and always without conviction. The CDU’s proposals would go even further, allowing indefinite detention pending deportation—a clear violation of fundamental rights that merely intensifies existing racist practices.

Already, policies such as payment cards, work prohibitions, and crowded shelters effectively strip asylum seekers of rights, resources, and social participation. These measures are compounded with criminalization processes, as control and surveillance by police and authorities systematically target migrantized individuals, pushing them deeper into precarious circumstances. For instance, receiving a fine or being held in pretrial detention can cost someone their job or housing opportunities.

Consider how this plays out: In border regions or police-designated “crime hotspots,” police can conduct checks without grounds for suspicion—opening the door to racial profiling. Through such practices, hundreds of thousands of “mass offenses” get reported annually—including, for instance, drug possession, shoplifting, minor fraud, and fare evasion. Offenses of this kind are often related to poverty, which is only further exacerbated by fines, probation, or imprisonment. Racist control practices and material exclusions help explain why foreign nationals appear overrepresented in criminal statistics, though structural causes rarely enter public discussion.

The debate is fueled by a series of moral panics

The assumed migration-crime connection stems largely from a series of moral panics that has revolved around racist stereotypes for years—and has been fueled especially in recent months by leading politicians from almost all parties. Moral panic describes a social process in which isolated incidents or behaviors—often crimes—are exaggerated into existential societal threats through emotionally charged political and media discourse. In this process, specific groups are stigmatized as threats to the moral order. As Stuart Hall and his colleagues demonstrated in the 1970s through their analysis of the “mugging” panic in Britain, this leads to the formation of an authoritarian “common sense”—a socially shared perspective that legitimizes increasingly harsh law-and-order policies while simultaneously diverting attention from underlying structural socioeconomic problems. For racialized persons in particular, such policies often mean nothing other than permanent violence by state institutions, which has long been normalized. This is also accompanied by an increase in racist violence by far-right perpetrators, which largely goes unaddressed.

Experts increasingly criticize this emotionally manipulated debate. Over 60 criminal law scholars recently condemned this debate for being “characterized by populist instrumentalizations and distorted media representations.” Media research shows that newspaper and television reports mention the origin of non-German suspects much more frequently than they are represented in the already distorted police statistics. Since the 2015/16 New Year’s Eve incidents in Cologne, a new trend of scaremongering has formed, which has been politically exploited ever since: criminologists observe that since 2016 there has been a noticeable shift toward exclusion-oriented criminal enforcement targeting foreign nationals—effectively transforming criminal law into a deportation tool.

Through “crimmigration”, criminal law acts as a deportation tool

Scholars use the term “crimmigration” to describe this troubling, increasing convergence of immigration and criminal law. Beyond standard penalties, non-German nationals face additional sanctions that follow a logic of exclusion—including deportation, prevention of status consolidation, or revocation/non-recognition of refugee status. “Crimmigration” thus creates a system of double punishment exclusively targeting migrants, with the list of offenses providing grounds even for expulsion continuously expanding. Today, even minor infractions resulting in fines can trigger deportation—for example if they are attributed to “antisemitic, racist, xenophobic, gender-based, sexual orientation-based, or other misanthropic motives.” This is a concerning prospect for pro-Palestine demonstrators especially, given the frequent, generalizing charges of antisemitism leveled under the banner of pro-Israeli Staatsräson, including (repeatedly) by chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz. CDU leaders like Carsten Linnemann now advocate for deportation after any two offenses, regardless of severity—even theft or fare evasion.

Against the background of increasing “crimmigration” and an ever-expanding carceral racism, a new migration policy is indeed needed. But a CDU-led government would likely intensify current approaches. The nominally left-of-center Ampel coalition recently introduced the most severe tightening of asylum law since 1993, and further tightening (such as the national implementation of European CEAS reforms) is certain to follow, with only the “how” left up for debate. What is truly needed is a fundamental shift that decouples migration questions from questions of safety and addresses both as questions of resource distribution. This means developing sustainable, socially-oriented approaches to safety that do not rely on racist control, surveillance, and punishment. It means asking how this wealthy nation can distribute resources to enable a good life for everyone who wishes to live here.