Enforcing Borders

Overview: The punishment system acts as a tool to enforce Germany’s violent anti-migrant policies. Criminal courts routinely presume “flight risk” for non-citizens, leading to long periods of pre-trial detention, and some judges even pressure defendants to leave the country. While we stress that racism in court can not be reduced to instances of discrimination, we repeatedly observe how anti-migrant prejudice evidently inflects judges’ interpretations of witness statements, as they pass character judgments on migrantized defendants for not learning German, question people’s claims to asylum, or accuse them of fraud. As migrantized people face systemic racism in the punishment system, criminal convictions can put their residency status at risk.1 Convictions also fuel racist myths about “criminal migrants”, which politicians exploit to further justify dispossessing and depriving migrantized groups—first among them often those who are criminalized.

Across the political spectrum, decision-makers in Germany are in agreement that migration must be combatted. Even though this is not a new development, considering that asylum rights have been under attack by parties of the right and center for decades, recent months have once again brought a surge of ever more restrictive asylum laws. Within a span of weeks in August and September 2024, the government agreed on a proposal to scale back social benefits for non-EU migrants, reinstituted deportations to Afghanistan, and decided to expand imprisonment and refusal of entry at German borders.2 These are just some of the latest examples of a long ongoing, large-scale attack on the fundamental rights of migrantized populations, which extends internationally. In April, the European Parliament passed reforms to the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), expanding inhumane fast-track proceedings and the incarceration of asylum seekers, including children.3

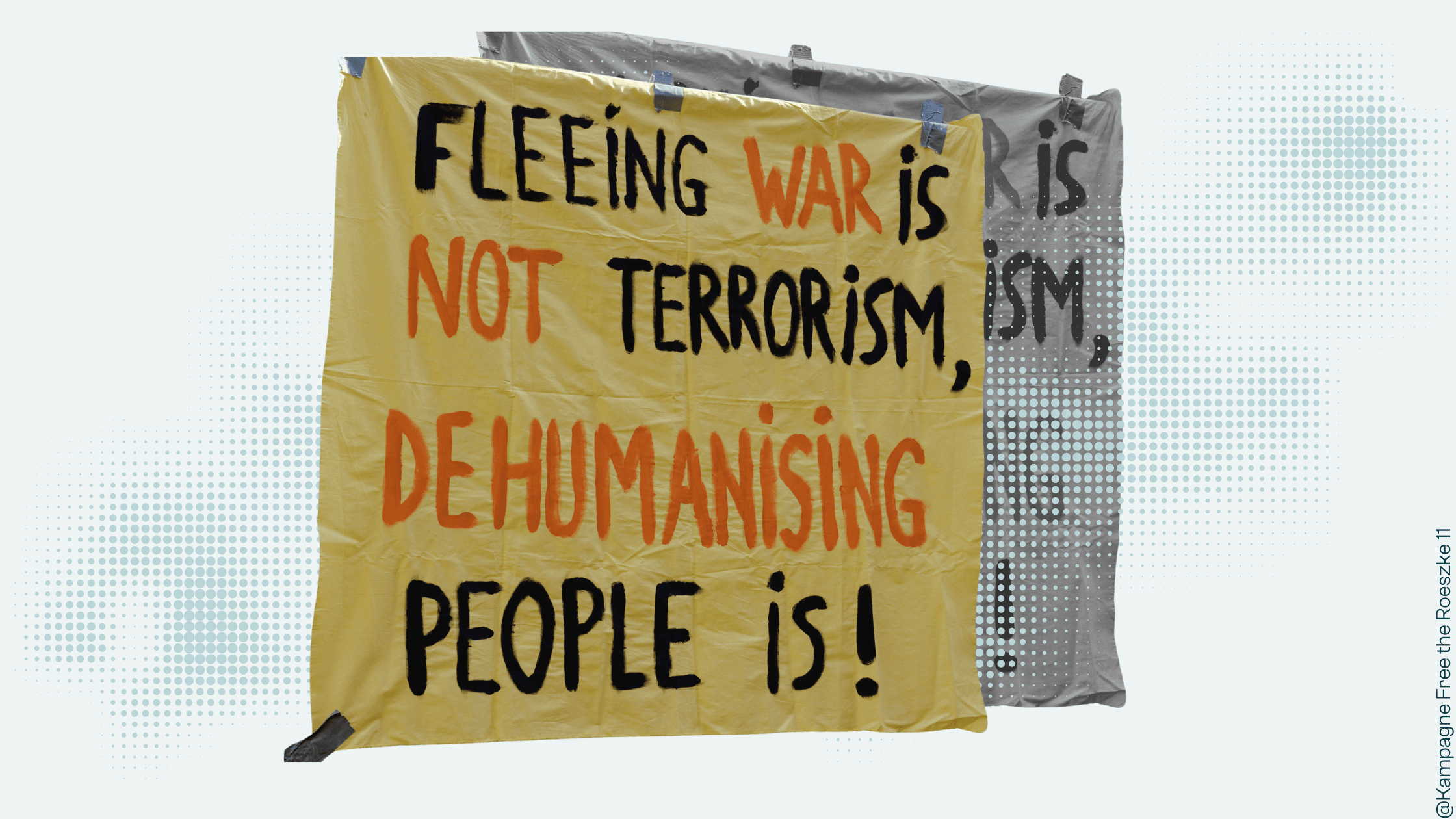

Anti-migrant policies such as these are meant to act as deterrents.4 They aim to make life harder for people who have decided that they can no longer live in their home country. Reasons for migration vary from person to person and context to context, but making such a momentous decision is often motivated by existential hardship—due, for example, to war, famine, climate catastrophe, or a lack of access to essential goods and services, including medication and medical treatment or other material resources necessary for survival.5 The worldwide distribution of material resources for people’s survival is shaped by the systemic forces of global capitalism. Put simply: The relative wealth of countries in the Global North depends on the exploitation of labor and the extraction of resources from the Global South—a relationship deeply rooted in the history and legacies of European colonialism.6 This means that the same structural conditions that render many people’s home countries unlivable are, in fact, what makes countries such as Germany so eminently livable and attractive to migrantized populations. At the same time, neoliberal globalization has led to the rise of a global informal working class at the very edges, or completely outside the system of global capitalism—so-called “surplus populations”, whose presence is concentrated in, though not limited to, the Global South.7

While relatively privileged migrants from wealthy countries face fewer obstacles in coming to Germany, anti-migrant policies aim to make conditions less attractive for a specific class of migrants: precarious and informal workers from the Global South. Politicians exploit anxieties among (though not limited to) the German working-class about competition for resources and cultural change to serve multiple purposes: it deflects attention from how global capitalism creates precarity for both migrants and citizens; it provides a simple explanation for complex social problems; and it helps justify increasingly harsh border and immigration policies. By constructing these migrants as culturally “incommensurable” and as threats to security and social services, politicians can present deportation and criminalization as solutions to economic and social insecurity, while maintaining a system that depends on exploitable migrant labor and manages racialized surplus populations.8 The state enlists the criminal legal system as a key mechanism in this process, using it to enforce borders beyond their physical form and to manage populations through criminalization.9

Under increasingly hostile conditions, large numbers of racialized migrants in Germany are routinely criminalized and end up in criminal courts. In our courtwatching, we see how courts act as a continuation of the country’s deterrence and close-door policies, enforcing borders by means of the criminal law. Many migrants who end up in court have already spent months in jail, before their case is even heard.10 This is because courts often presume “flight risk”, which leads to people without German citizenship accounting for 60 percent of the people held in pretrial detention.11 At times, judges use the threat of prison to pressure defendants into leaving the country.12 In other instances, anti-migrant prejudice evidently inflects judges’ interpretations of witness statements, as they pass character judgments on migrantized defendants for not learning German, question people’s claims to asylum, or accuse them of fraud.13

Practices like racial profiling—especially in the form of “hotspot” logics, where police label areas with high densities of working class and working poor migrant populations as so-called “crime hotspots”—can also be viewed through the lens of enforcing borders:14 Not only does law enforcement specifically target racialized and migrantized communities; their targets are often barred from participation in the formal economy through the withholding of work permits, which can produce dependence on extralegal sources of income.15 This means that the criminalization of migrants is deeply connected to the criminalization of poverty. The systematic restriction of migrants’ access to material resources enables the disproportionate policing and punishment of migrant populations to appear justified on grounds of “crime control”, when what is actually happening is that criminalization acts as a form of migration control. Through fines and other forms of punishment, this criminalization further contributes to the dispossession of migrants.

Punishment by the criminal legal system also poses a severe threat for many migrantized people’s residency status, marking them as deportable subjects.16 Judges often appear to be unaware of this—since migration law and criminal law are different areas of knowledge—, or they simply do not care (or worse). Adding insult to injury, the mass criminalization of migrantized populations for low-level offenses fuels the myth of the “criminal migrant”—a racist construction that political actors on the right and in the center exploit to legitimize the extensive deprivation of rights for immigrants and asylum seekers. Criminalization thus acts as a mechanism for stripping migrantized populations of their rights and removing them from the country—and for legitimizing ever more drastic and extensive policies to facilitate this.17

In our archive, we label cases with the “Enforcing Borders” tag when we observe how people’s interactions with the criminal legal system are shaped significantly by their residency and/or asylum status. This includes, for example, when people are criminalized who have very little to no access to legal means of income; when people face long periods of pretrial detention on no other apparent grounds than their residence outside of Germany or foreign citizenship; when people face structural problems due to migrating which are neglected in the courtroom; when members of the court express prejudice against migrantized populations and asylum seekers, or suggest to defendants that they would be better off leaving the country; and when the severity of a sentence is likely to impact a person’s asylum status. These are just some of the ways in which criminal courts work to enforce borders and which we continue to monitor and document.

Citations

- 1

In the context of German law, the legal scholar Cengiz Barskanmaz offers a useful definition of racism, which he describes as a “historically rooted and structural social phenomenon that expresses a relationship of power and dominance and consequently produces, legitimizes and perpetuates material and symbolic exclusions.” ‘Rassismus, Postkolonialismus und Recht – Zu einer deutschen Critical Race Theory?’ 41 Kritische Justiz 3, 297. The philosopher Charles Mills illuminates the systemic character of this phenomenon, defining racism as “a political system, a particular power structure of formal or informal rule, socioeconomic privilege, and norms for the differential distribution of material wealth and opportunities, benefits and burdens, rights and duties.” The Racial Contract (Cornell UP 1997), 22. To put a finer point on how this system operates in a specific geographic context, we draw also on the geographer and prison scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (University of California Press 2007), 28.

- 2

‘Regierung einigt sich auf Sicherheits- und Asylpaket’ (Tagesschau, 29.8.2024) <https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/innenpolitik/bundesregierung-massnahmen-solingen-100.html>; ‘Abschiebeflug nach Afghanistan gestartet’ (Tagesschau, 30.8.2024) <https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/innenpolitik/abschiebeflug-afghanistan-asylpolitik-100.html>; Rasmus Buchsteiner, ‘Bundesregierung plant Haft für Geflüchtete an der Grenze’ (Spiegel, 10.9.2024) <https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/plaene-beim-migrationsgipfel-bundesregierung-plant-haft-fuer-gefluechtete-an-der-grenze-a-c5917be5-47c7-4de5-906e-a99d08d72b39>.

- 3

‘GEAS-Reform im EU-Parlament: Historischer Tiefpunkt für den Flüchtlingsschutz in Europa’ (Pro Asyl, 10.4.2024) <https://www.proasyl.de/news/geas-reform-im-eu-parlament-historischer-tiefpunkt-fuer-den-fluechtlingsschutz-in-europa/>.

- 4

See, for instance, Matilde Rosina, The Criminalisation of Irregular Migration in Europe (Springer Nature 2022).

- 5

‘Fluchtursachen’ (UNO-Flüchtlingshilfe) <https://www.uno-fluechtlingshilfe.de/hilfe-weltweit/themen/fluchtursachen> Accessed 7 November 2024. See also Sonja Buckel and Judith Kopp, Fluchtursachen: Das Recht, nicht gehen zu müssen, und die Politik Europas (Bertz + Fischer 2022).

- 6

For a systemic analysis, see, for instance, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations (OUP 2022). For an empirical study, see, for instance, Hickel, Dorninger, Wieland, Suwandi, ‘Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015’ (2022) 73 Global Environmental Change <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467> Accessed 7 November 2024.

- 7

See, for instance, Mike Davis, ‘Planet of Slums’ (2004) 26 New Left Review March-April.

- 8

Vanessa E. Thompson, ‘Policing the Surplus Crisis, Carceral Racism and Abolitionist Resistance in Germany’ (forthcoming, 2025).

- 9

See Harsha Walia, Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (Haymarket Books 2021); Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor (Duke UP 2013).

- 10

Case 3, Case 14, Case 22

- 11

‘Fluchtgefahr als Haftgrund: Nicht alle sind gleich’, taz, September 29, 2024, <https://taz.de/Fluchtgefahr-als-Haftgrund/!6036610/>. See also ‘Personen mit Untersuchungshaft nach Staatsangehörigkeit’, Statistisches Bundesamt, November 10, 2021, <https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Staat/Justiz-Rechtspflege/Tabellen/sonderauswertung-untersuchungshaft.html>.

- 12

- 13

- 14

See also Svenja Keitzel und Bernd Belina, ‘“Gefährliche Orte”: Wie abstrakte Ungleichheit im Gesetz eingeschrieben ist und systematisch Ungleichbehandlung fördert” (2020) 110 (4) Geographische Zeitschrift.

- 15

See also Mohammed Ali Chahrour, Levi Sauer, Lina Schmid, Jorinde Schulz, Michèle Winkler (eds), Generalverdacht: Wie mit dem Mythos Clankriminalität Politik gemacht wird (Nautilus, 2023).

- 16

Criminal offenses resulting in fines of more than 50 or 90 daily rates can establish grounds for expulsion (§54 of the Residence Act), serve as a disqualification for naturalization (§8 of the Residence Act), affect the discretion of the immigration authorities in granting a work permit (§25b of the Residence Act), and prevent the following residence permits: toleration for vocational training (§60c (2) of the Residence Act), residence permits following vocational training (§19d of the Residence Act), and a child’s settlement permit (§35 (3) of the Residence Act).

- 17

See also Ma‘ayan Ashash und Danna Marshall, ‘Antisemitismus als Grenzmechanismus’ (2024), 135 Bürgerrechte & Polizei/CILIP.

Cases from our archive

Case 22

A man is held in pretrial detention for months and sentenced to a fine of several thousand euros for selling cannabis. Although at the time of the trial, the legalization of cannabis consumption and further decriminalization of possession and supply is imminent, the court strongly condemns the defendant's actions. The prosecutor described them as “extremely reprehensible”.

Case 27

Shortly after a wave of populist outrage over a knife attack, a man convicted of attempted assault with a weapon based on little evidence appeals his sentence. At the appeal hearing, the environment is hostile, with the recent knife panic in the air: the defense is hindered from questioning witnesses while the judge and prosecutor cherry-pick testimony in an effort to justify continuing to jail the defendant pretrial, which would also facilitate his deportation. Even after a second appeal hearing does not reveal evidence sufficient to convict, the judge and prosecution insist on a high prison sentence, just two months short of his original one. The defendant is released after the second hearing because he has already served his sentence in pretrial detention.

Case 20

Three young defendants are summoned to fast-track proceedings (Schnellgericht) for a low-level theft case. Because the court has not lined up an interpreter for one of them, he will not be heard and instead will be sentenced with summary proceedings (Strafbefehl), meaning he will receive his sentence in the mail. After a quick hearing, the other two are each punished with €600 fines.

Case 26

A young man is on trial for theft. During his trial, he is informed that his sentence will be high because he had a knife at the time, though the evidence does not show that it was used during the offense. The judge threatens the defendant with jail time. Without a lawyer to consult, he appears to have little choice but to accept the harsh sentence and put up with the judge’s insinuations that he steals for the purpose of reselling – just like unnamed “others” the judge refers to.

Perspectives

Criminalized: The Anti-Migration Debate Fuels and Legitimizes Systemic Racism

Anthony Obst, Justice Collective

Fueled by media coverage of isolated violent incidents, a troubling consensus has emerged that presents increasingly severe law-and-order measures as the only solution to perceived insecurity supposedly caused by immigration. This obscures the violent realities of racist criminalization.

Refugees in Germany: The omnipresent border regime

Britta Rabe, Grundrechtekomitee

Even after surviving perilous journeys to reach the EU – which can include pushbacks, beatings, and torture – refugees face an exclusionary system within Fortress Europe that makes their arrival difficult or even impossible. The EU border regime extends all the way into Germany, permeating society invisibly yet tangibly for those who are excluded.