Case 8

| Case Number | 8 |

| Charge | Theft |

| Defense Attorney Present | No |

| Interpreter Present | Yes |

| Racialized Person | Yes |

| Outcome | Probation |

For stealing around €100 worth of clothes and groceries from a supermarket, a young woman is sentenced to three months in prison (on two years of probation) and 80 hours of unpaid work. During the trial, the judge acts hostile towards her and accuses her of asylum and social benefit fraud.

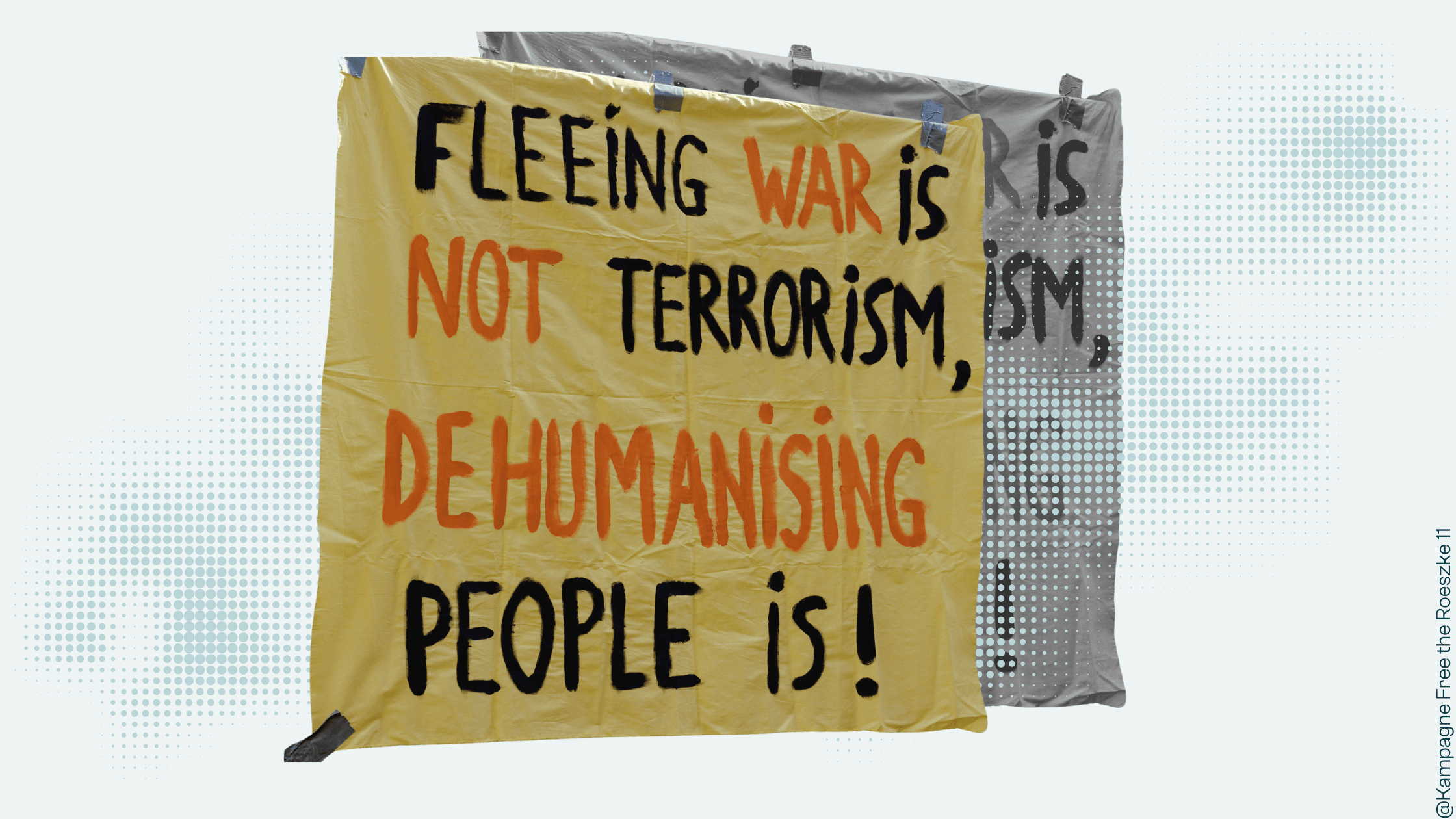

The judge seems to form a negative image of the accused woman in this case from the very beginning. Her questioning reflects racist prejudice against migrantized people, as she seems to suspect the defendant of illegally claiming social benefits. This impression is confirmed when the judge openly levels fraud accusations at her during the sentencing, alleging “criminal energy”. The judge ignores that what was stolen was mostly food for the woman’s children, and that people in Germany seeking asylum receive limited state support and often have no other way to secure an income.

The sentence in this case was particularly harsh, in part argued on the basis of the woman’s past offenses for similar things. That courts weigh past offenses so heavily often means that people are punished for their structural circumstances repeatedly, and ever more harshly.

The defendant is a young woman, who enters the courtroom with a baby in a stroller and a man accompanying her and tries to sit down on one of the benches for the public. As she enters, the judge grimaces and mutters under her breath while the translator tells the defendant that this is not her place. There appears to be some confusion as to whether the man and the baby can stay, with the translator suggesting they must leave and the judge confirming. It is only once the two have left the room (the woman still unsure what to do), that she is told to sit down at the front of the room.

The judge asks about her personal details. She questions the woman in detail about having an alias name (perhaps suspecting her to have a fake identity) but the woman explains that the different names listed for her are due to marriage. The judge questions whether the marriage was according to German law. The woman says that she has children and that she has been in Germany for a few years. When asked how she earns her living, the woman says she has applied for asylum. The judge then asks her what she wants in Germany and whether she was persecuted in her home country.

The charge states that the woman is accused of stealing groceries and clothes from a supermarket, together with another person who also has a case against him. The woman confesses and apologizes repeatedly, testifying that she stole the goods for herself and her children. The judge replies that she cannot apply for asylum in Germany and then “continuously commit crimes” (“andauernd Straftaten begehen”), noting past theft offenses.

When the judge announces the sentence, she alleges that the defendant has no actual claim to asylum and that she is only in Germany to collect money payments, housing, and other benefits. The judge accuses the woman of harboring what she calls “criminal energy”, framing her as an asylum and social benefits fraudster. She frames the probation sentence as a way to educate the woman, threatening prison for any subsequent offense, emphasizing how this would be bad for the woman’s children. The judge also states that 80 hours of unpaid work will not pose a problem for the woman in taking care of her children.